Blog for the Cycling Community by Clara Glachant, PhD Candidate at Eindhoven University of Technology.

Clara Glachant is a PhD Candidate at the Technology, Innovation, and Society research group of Eindhoven University of Technology. Her research focuses on the perceptions and representations of micromobilities in the context of the transition to more sustainable mobilities in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. This blog presents some insights from her research paper on moped stereotypes, co-authored by her supervisor Frauke Behrendt.

Spatial Conflicts

As I am cycling in Breda, the Netherlands on a quiet Saturday morning, a moped loudly whizzes past me. How many times, ever since I moved to the Netherlands five years ago, have I been annoyed, as a cyclist, by moped riders disturbing my peaceful cycling routine? For just a moment, I remind myself: yes, this moped rider is allowed on the cycling path, and no, they did not forget their helmet (required for light mopeds since January 1, 2023). As I resume cycling after this frustrating encounter, I can’t help but have negative images of moped riders in mind. This incident is just one of many, illustrating the ongoing challenge of mopeds and bicycles sharing Dutch cycling paths. The Dutch case is especially pertinent as many European cities encourage a shift away from car use and to more micromobilities such as (e-)bikes, e-scooters, and e-mopeds. If micromobilities can contribute to a transition to more sustainable mobilities, the question of where should these modes ride remains – as they often compete for space with other sustainable modes such as cycling and walking. (Micromobility refers to small human-powered or electric vehicles operated at low speeds, Behrendt et al., 2023).

The Dutch Context

While some cities grapple with the sudden emergence of micromobilities and spatial conflicts they create—evident in the banning of e-scooters in Paris–the Netherlands has a long tradition of accommodating various forms of micromobility in public space. From the introduction of mopeds in the 1950s (Dekker, 2021) to the recent surge of rental schemes, the coexistence of bicycles and mopeds on Dutch cycling paths has sparked forceful debates among policymakers, leading recently to bans of light mopeds from cycling paths in Amsterdam and Utrecht. Conflicts between bicycles and mopeds highlight the spatial complexity of shifting to more micromobilities in the Netherlands – especially while the dominance of cars in public space remains unchallenged.

The Bad Moped User vs. the Good Cyclist

As I delved into the perceptions of moped users for my research, my findings mirrored my impressions following my encounters with mopeds on cycling paths. Mopeds are often cast as “others” on cycling paths – cast as fast, loud, and occasionally pushy intruders. What struck me most is the ambiguous position of mopeds in public space: should they ride on the road or the cycling path? The answer isn’t always clear. Riders, unsure where they’re allowed, choose the cycling path when they should instead ride in the street. That being said, this polarization between cyclists and moped users isn’t simply black and white – not all moped users are problematic and not all cyclists are virtuous. One letter to the editor, for instance, points to the media coverage of “cyclists raging against moped riders,” which turns into “blind hatred of the moped rider.” (Quote translated from Dutch to English by the author)

Exploring Moped User Stereotypes

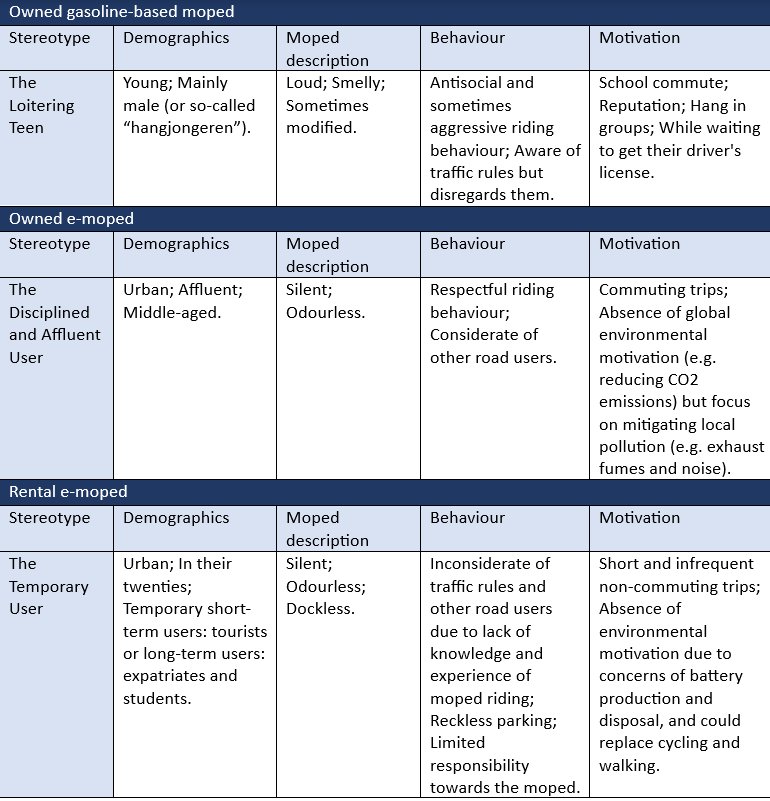

To better understand the diversity of conflicts between mopeds and bicycles on cycling paths, I looked into the stereotypes that often shape perceptions of mopeds and their riders. Stereotypes are cognitive shortcuts used to simplify the complexity of reality. Based on interviews and press articles, I mapped the stereotypes associated with three categories of mopeds found in the Netherlands: privately owned gasoline-based mopeds, privately owned e-mopeds, and rental e-mopeds. These are presented in the table below.

Stereotypes Embedded in Preexisting Identities

In my research, I discovered that gasoline mopeds evoke more stereotypes than owned and rental e-mopeds, probably due to their wider use and longer existence in the Dutch landscape. I noticed that these stereotypes often relate to social status. Take, for example, class-based stereotypes. On one end, there is the stereotype of the well-off female student riding around Amsterdam on a sleek Vespa, with her friend in the back. On the other end, there’s the young man living in the outskirts of the city, probably working in construction, riding a second-hand modified moped. He might bend the rules a bit more but still respects others on the road. These (purposely) stereotypical users show how perceptions are tied to identities like class, age, or place of residence, which often involve power dynamics. Such stereotypes further complicate how the limited space granted to micromobilities, such as mopeds, is negotiated.

What about the Car?

My study of moped rider stereotypes also reveals another fundamental issue: the focus on moped versus bicycle conflicts overlooks and obscures the larger challenge posed by the dominance of cars in public space. The limited allocation of space for both mopeds and bicycles exacerbates tensions, highlighting the urgent need to address the elephant in the room – the car. We then argue that the key to transitioning to more sustainable mobility is challenging the dominance of automobility and giving more space to micromobility

These findings have implications for policymaking. At the European scale, if micromobilities are to be part of the solution for transitioning to more sustainable mobility, policies must expand space for micromobility in cities to avoid conflicts between existing and new forms. This should be done by repurposing spaces currently allocated to cars, following the example of Paris’ Seine riverbank. In the Netherlands, municipalities could ease moped-bicycle conflicts by limiting moped use to roadways within urban areas, and lowering speed limits to 30 km/h as advocated by organizations such as the Dutch Cyclists’ Union.

All in all, the next time a moped passes me on the cycling path, I’ll take a step back and try to see the bigger picture. Rather than just getting frustrated by moped riders, let’s shift the focus to the real culprit: the automobiles that occupy 55% of Dutch urban space.

Pictures by the author.

You must be logged in to post a comment.