DCA Blog by Ruth Oldenziel, professor at the History Division of the Technology Innovation, Society Group at Eindhoven University of Technology.

Bicycle scholarship has been booming since 2009. Perhaps the economic crisis that brought the U.S. automotive industry on its knees had something to do with it. In the 2008 election campaign, the bicycle lobby even got Obama on a bike—helmet and all.

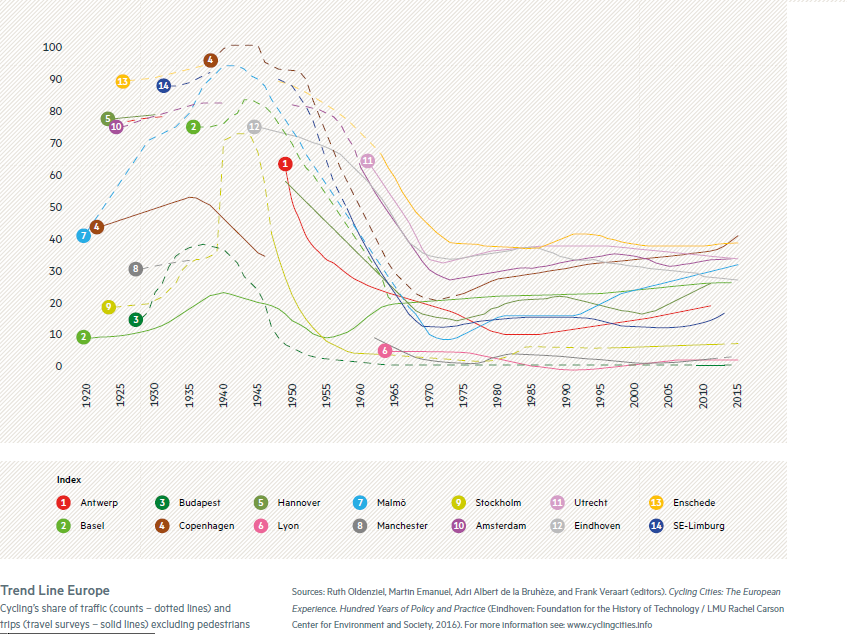

To innovation scholars, historical scholarship offers an attractive perspective on how to make a transition to a more sustainable future. Three decades ago, a young Dutch PhD student in innovation sociology at Twente University, Wiebe Bijker, began using the early history of bicycles to make a larger theoretical point for innovation studies: users really matter in shaping our innovations. Bijker famously argued macho men loved their high bi’s as adventure machines, but it was relevant social groups like women, the young, and the elderly, who helped create a demand for safety bicycles. That demand radically changed the bike to what it looks today: a useful form of mobility for the many rather than a dangerous toy for the few. More recently, others also happily exploited its history. For Elizabeth Shove cycling history’s shows innovation is not always about the new and the spectacular. Mobilizing historians’ work on cycling of De la Bruhèze and Veraart, she argues that innovation studies also need to look how and why innovations disappear and reappear. A long-term perspective of history makes that visible.

To the frustration of my fellow cycling historians, these great scholars have neither been truly interested in bicycles or in its history—and the hard archival digging that the historian’s craft requires. Most mobility histories merely treat bicycles as a bump in the inevitable innovative road for cars. Swiss historian Monica Burri rightfully questioned the idea. Frank Veraart identified the Dutch Touring Organization as a key stakeholder in shaping innovation—a point Katrine Ebert (Radelnde Nationen) further documented in comparing the Netherlands and the Germany fifteen years later. An international group of historians offers the role of policy makers in the hundred-year boom, bust, and recovering of cycling in many European cities. And Carlton Reid and James Longhurst have since given us the delightful century-long cycling histories of the U.S. and the U.K. with provocative titles like These Roads Were not Built for Cars, Bicycle Boom, and Bike Battles to show how middle-class cyclists and their organizations helped create the road infrastructures we have today.

On the eve of the inauguration of a new U.S. president, the fossil-fuel lobby is back with a vengeance. For one, there is little chance Trump will ever be caught on a bicycle—with or without a helmet. Yet, 2017 is going to be rich year: the bicycle history scholarship is booming as never before. And here to stay.

You must be logged in to post a comment.